Building a Business Case for Medtech Transformation

Part 2: How to think about risk in a medtech business case (Part 1)

Execution risk relates to what might go wrong in a project. Good project management methodology—and choosing the right kind of software—can mitigate execution risk.

What about underlying business risk?

Reducing compliance risk and business risk is often an investment rationale, but it can be tricky to “price” the risk. There aren’t actuarial tables that can quantify this kind of risk the way there are for car insurance or life insurance.

Every medtech manufacturing and quality leader plans to have zero recalls. Yet, recalls do happen. And when they happen, there’s a significant cost—both financial and reputational—to remediate them. The same applies to compliance fines.

Creating baselines can help. While of course you plan to have no recalls, if in fact you’ve had 2-4 recalls per year on average over the past five years, you can use that to baseline. Let’s imagine these are large class I product recalls with an average cost of $20 million to address. Now, your baseline recall cost is $60 million per year. If that’s the case, your controls need improvement, and you have the foundation of a business case. You could complete a similar analysis for compliance fines. If you’re concerned about controls but you haven’t had major issues, you can still look at comparables in the industry and estimate a cost of risk that way

Regardless, quantifying the cost of failure, either with your own data or with reference to comparables, helps make the case. It’s also important to note that compliance costs have risen over the past decade due to more complex supply chains, stricter regulatory requirements, and increased litigation.

In addition to pricing risks as best as you can, it’s also helpful to build out some story points. Have you had a lot of near misses? You can gather details by talking to the people who are running the operation and are experiencing the pain of bad processes, systems, or controls. These true horror stories about what went wrong, or almost went wrong, help bring the gravity of the problems to life for senior leaders, who are often removed from the day-to-day.

Distinguishing between hard and soft benefits

The difference between hard benefits and soft benefits is one of the most misunderstood aspects of defining business value—outside of CFOs and their teams. Since CFOs typically approve major investments, it’s important to understand and explain the benefits case in their language.

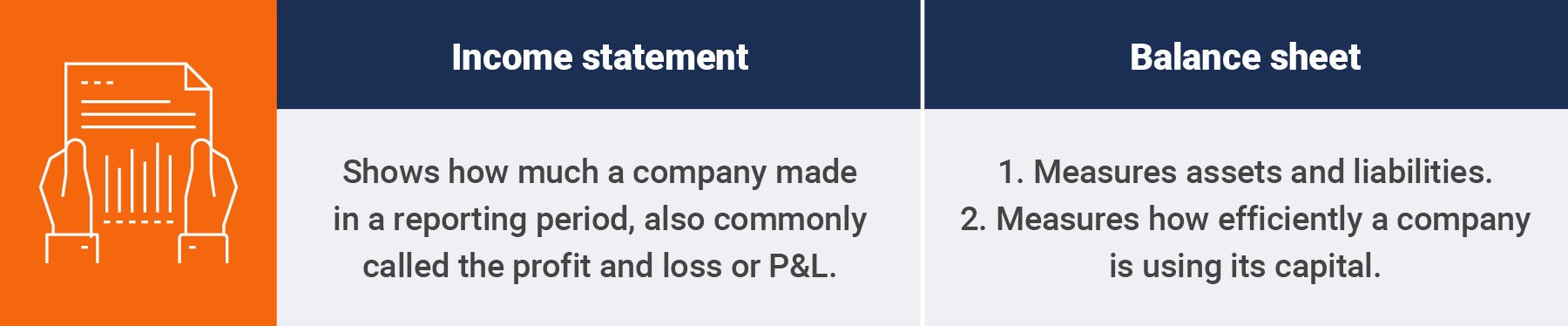

Businesses use two major “schedules” to measure their financial performance:

The income statement is made up of top line revenues, minus the cost of goods sold (cost to manufacture or service), minus sales general and administrative costs, minus taxes (and sometimes special items).

Top line revenues minus cost of goods sold is the gross margin, and the gross margin minus sales general and administrative costs is the net margin or operating margin.

The balance sheet consists of all the company’s long and short assets (including factories, cash, accounts receivable, intellectual property, etc.) and liabilities (including debt, accounts payable, etc.).

From a finance lens, hard benefits show up in the P&L, the balance sheet, or both. Soft benefits or avoidance benefits do not show up.

This means that a very strong financial business case will improve revenue or gross margins or net margins on the P&L. That is, we need more revenue or less cost—either cost of good sold or sales general and administrative costs. Or we need to improve asset utilization or reduce assets on the balance sheet to free up capital.

For most CFOs, being more efficient or improving the user experience does not equal a hard benefit, unless we are not physically improving revenues, costs, or asset utilization. Usually, these soft benefits or cost avoidance will not count towards return.

It’s still worthwhile quantifying soft benefits as well as we can and they are still a good story point, but hard benefits—especially P&L improvements in revenue or margins—rule in finance. That’s why wherever possible you should try to reframe soft benefits like “quality and regulatory team efficiency” as hard benefits like “faster change control reducing the cost of goods sold by qualifying more cost effective raw materials in our supply base”.

How to sustain medtech business value over the long term

Once you’ve defined your business case and received the investment, you’re all done, right?

In fact, that’s just the beginning.

Just like the metaphor of the house investment, once you have the funding and you buy the house, then someone lives in the house and gets the benefits of living there.

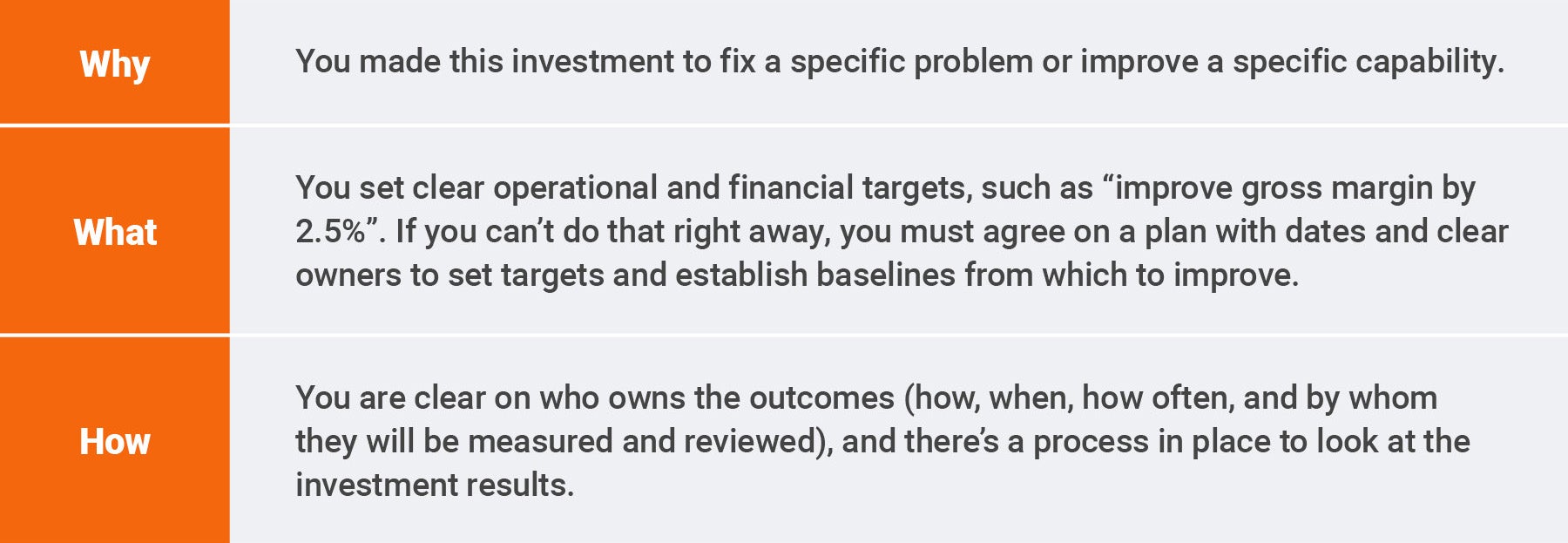

In the same way, when you planned a digital transformation project, you promised the business some new benefits, and when that project is complete, you have to measure the outcomes. That is how you live up to the promises you made and breathe life into the transformation strategy.

Doing this is difficult and requires some attention. Most medtech companies struggle in the value realization phases of a transformation, and there are several typical reasons for this:

- Projects are tiring and people want to “get back to normal” rather than embedding the improvements

- You are asking people to work in new ways—this change management is hard

- Despite your best efforts, you may not have captured the value or the baselines sufficiently

- There are often accountability gaps in who owns the outcomes. Who will drive the process to make sure that the organization delivers the benefits?

- New metrics can change performance incentives. Misaligned incentives encourage people to work in the old way or some tangential way

There are three key moments in the life of a transformation investment. In the house metaphor those are 1) when you decide to buy the house, 2) when you actually buy (or build it), and 3) when someone moves in and lives in it.

To sustain value, you still have to focus on the why, the what, and the how.

Finally, you need sponsorship and alignment. While CFOs are often tough on investment approvals—that’s their job after all—they are excellent sponsors to hold the organization accountable. The same goes for senior leaders in operations, sales, and HR. The right steering team or governance structure is key to making sure an investment delivers on the business value envisioned in the strategy.

To download a PDF version of parts one and two, click here.