Blog

Dispelling BYOD ePRO Myths in Clinical Trials

Apr 05, 2023 | Jim Munz

Apr 05, 2023 | Jim Munz

When I was young, I sometimes got spooked by ‘the thing in the closet.’ Once I got the idea there might be a boogeyman, it was easy to imagine it hiding amongst the shadows. Yet, when the morning came, it was always gone, and I understood it was only jackets hanging on the rail. This often comes to mind when discussing bring your own device (BYOD) in clinical research. There are many myths and assumptions blended in with requirements for using patient devices. It’s time to shed light on BYOD so the industry can execute faster, more efficient clinical trials.

With over 6.8 billion smartphone users globally, you could be forgiven for assuming that clinical trial participants would be able to use their own devices to conduct study activities. However, industry has been slow to adopt BYOD, due in part to myths that have evolved around the approach. As a result, the vast majority of ePRO trials still rely on provisioned devices.

In this series of blogs I will review common objections, discuss their merits, and highlight where the arguments are no longer valid. The first topic is data quality and security.

Data quality and security considerations for BYOD ePRO

Data quality and security are paramount when collecting clinical trial data. One of the common myths about a BYOD approach is that it may increase data quality and security risks. However, although it may seem easier to control the data collection process with provisioned devices, experience shows this is not the case.

Maintaining data quality and integrity

Clinical trial participation can be time-consuming and confusing, so it is important to make study actions as easy as possible for patients. The more seamlessly ePRO fits into patients’ lives, the more likely they are to complete surveys and assessments at the required time. When patients use provisioned devices, they are more likely to miss entries if they are having a busy week or go on vacation. With a BYOD approach, patients automatically carry their devices wherever they go and can check them regularly.

The benefits of using patients’ own devices go beyond eliminating missing data points. Patients are more comfortable with the device controls, operating system, and settings (e.g., larger text for the visually impaired). This makes completing ePROs easier and removes the need to train on a new device. However, if they are required to use an unfamiliar device, it can lead to a poor user experience and greater opportunity for errors.

I recently experienced the frustration of switching operating systems first-hand. Our family are iOS users, so my son was struggling to complete assignments using the Chromebook his school provided. I purchased one for home so he could practice using it but, even though I have worked with technology for my whole career, I struggled to navigate the differences. The set-up process was extremely frustrating and helped me understand why he took much longer to complete his assignments on an unfamiliar device.

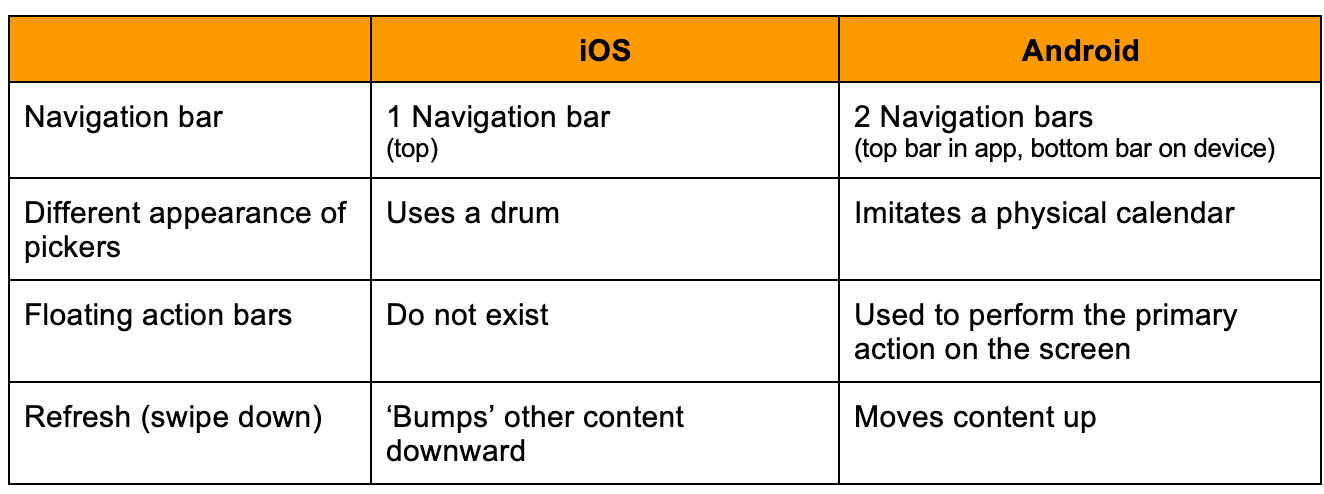

Examples of differences between iOS and Android operating systems:1

Managing security

All devices need to be kept up to date with the manufacturer’s security updates. You could be forgiven for assuming it is easier to keep devices up to date with a provisioned approach, but this isn’t the case.

When selecting a provisioned device, vendors typically opt for a single, cost-effective device. These are commodity devices incorporating low-cost hardware components and open source software that may not maintain security best practices.2, 3

Device selection and validation often takes 6-12 months, but low-cost devices are only sold for a short period before they are updated to the next model. This adds complexity as sourcing sufficient devices is extremely difficult, import certification may not be maintained, and security updates may end prematurely.

This has a significant impact on study conduct over time as devices become slower and less responsive, creating patient dissatisfaction. Study teams also have to spend increased time trying to troubleshoot issues and replace unresponsive devices.

So how does security differ when using the patient’s own device? Firstly, patients are more likely to have a current device with up-to-date security. Then, the app must maintain strong security disciplines, full encryption, and the ability to transfer data as soon as possible so it is not stored locally.

Biometrics offer the potential to further strengthen security when using a BYOD approach. Although use of biometrics (e.g.,fingerprints and facial recognition) is now common, it has not been possible to incorporate this layer of security on provisioned devices. To do so would be extremely complicated for vendors, sites, and patients, but also would require patients to share highly personal information on a device they do not own. However, with BYOD it is natural to use biometrics to support the login process, just like consumer apps.

One size does not fit all

When it comes to data quality and security, there is arguably greater risk associated with provisioning devices than when allowing participants to use their own. Requiring participants to use unfamiliar devices to complete study activities requires initial training, followed by reinforcement to ensure that forms are filled out correctly. Conversely, a BYOD approach gives participants the freedom to complete study activities on their own device, which is more likely to be kept on, charged, and updated regularly. It also provides a familiar interface so patients are more likely to enter responses correctly.

In my next blog, I discuss why BYOD doesn’t just improve patient experience, it also opens up the opportunity to improve site experience as well.

References

1. 32 design differences between iOS and Android apps

2. Snapdragon chip flaws put >1 billion Android phones at risk of data theft

3. Critical Chipset Bugs Open Millions of Android Devices to Remote Spying